|

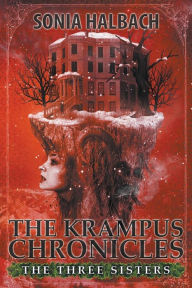

| The Three Sisters (The Krampus Chronicles Book 1), by Sonia Halbach This book was provided by the publisher through NetGalley in exchange for a fair and honest review. |

|

| 4 snowflakes for creativity, action, romance, and fun |

|

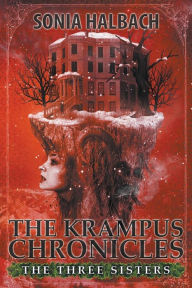

| The Three Sisters (The Krampus Chronicles Book 1), by Sonia Halbach This book was provided by the publisher through NetGalley in exchange for a fair and honest review. |

|

| 4 snowflakes for creativity, action, romance, and fun |

|

| The Martian, by Andy Weir, narrated by R. C. Bray |

|

| 4.5 stars for interest level and superb execution |

|

| 3.5 snowflakes for unique world building and Meaning |

As an afterthought – I would like to post this Twitter conversation:

|

| The Tide, by Anthony J Melchiorri, narrated by Ryan Kennard Burke |

|

| I decided to give this book four stars despite the fact that there wasn’t a satisfying ending. The science was excellent and it was just what a biotech thriller should be. |

The Girl from the Well, by Rin Chupeco

Genre: Teen Horror / Suspense

Reason for Reading: This book was provided by the publisher, Sourcebooks Fire, through Netgalley in exchange for an honest review.

Summary: Tarquin (Tark) Halloway has been haunted his entire life. With a mentally ill mother and a caring father who works too much, he feels he has no one to talk to about the strange lady that slinks through mirrors and makes Tark do terrible things. But when he meets a roaming spirit, Okiku, they both begin to remember what it is to be human. With the help from Tark’s cousin Callie, Okiku and Tark must rid himself of his haunting.

My Thoughts: Let me tell you, if I had read this book when I was 14, I would have been sleeping with the lights on for weeks. The spookiness / imagery is reminiscent of Japanese horror films that The Grudge (Ju-On: The Grudge) and The Ring (Ringu) were based on. (Have you seen the originals? Not the American remakes. Watch the real thing. Darn spooky! That’s what The Girl From the Well is like.) Same evil-ghost-child-with-long-creepy-hair-staring-at-you-in-crazy-fast-did-that-actually-just-happen-flashes feel to it.

Part of Rin Chupeco’s spooky genius is her narration style. The story is narrated from the POV of the ghost, Okiku. Often, it reads like a 3rd person omniscient narrative, because Okiku mostly observes rather than acting. I often forgot I was reading a first person POV, and then suddenly Okiku would say something in the first person, and it was like she had just appeared out of nowhere. Like a ghost. Spooky. And then, sometimes Okiku would describe herself in the third person – a description of a ghost as Callie or Tark would have seen. This gave Okiku’s character a sense of otherness. She felt inhuman. Ineffable.

Overall, I think this was an fantastic book, and I look forward to reading more of Chupeco’s works. I miss the old days when ghosts were ghosts and monsters were monsters. I applaud Chupeco’s work as one more for the #reclaimhorror team. (Ok, I just made that hashtag up, so technically she’s the first on the team. But it’s all good.)

Rin Chupeco: Despite uncanny resemblances to Japanese revenants, Rin Chupeco has always maintained her sense of humor. Raised in Manila, Philippines, she keeps four pets: a dog, two birds, and a husband. She’s been a technical writer and travel blogger, but now makes things up for a living. The Girl from the Well is her debut novel. Connect with Rin at www.rinchupeco.com.

Blood Ties, by Garth Nix and Sean Williams

Genre: Middle Grade Fantasy / Adventure Series

Reason for Reading: I’m already reading this series, of course, but I was happy that Scholastic provided an ARC through Netgalley in exchange for an honest review.

Synopsis (May contain some light spoilers for earlier books in the series): Meilen has run away from the Greencloaks to search for her father in her homeland of Zhong. Conor, Abeke, and Rollan quickly follow – they hope to recover their friend and get the Slate Elephant talisman from Dinesh, the Great Elephant. But Zhong has been conquered, so the kids must fight through armies of enemies to find what they seek. The Devourer is gaining power, and he will stop at nothing to take over all of Erdas with his nature-defiling bile.

My thoughts: Another great installment of the series. And they just keep getting better and better! (Not, of course, because the authors are changing, but because the plot and characters are developing as the series progresses.) Like in the earlier books, Blood Ties shows the power friendship – of working with your team rather than trying to fight evil alone. It encourages trust – of your partners, your friends, and the power of Good to conquer Evil. Most of all, the story is fun. It’s a delight to watch as the kids’ distinct characters develop, and how each character adds to the dynamics of the team. The world-building is also a lot of fun – it has both a familiar and a novel taste. For instance, Zhong is the Erdas-equivalent of Asia. The comparison is undeniable, and yet Zhong’s culture and scenery are also delightfully unique. And, of course, this book is filled with adventures, intrigue, and battles – which any lover of middle grade fantasy / adventure books craves. I’m looking forward to the release of the next book in the series, Fire and Ice, in July.

Jesus, the Middle Eastern Storyteller, by Gary M. Burge

Genre: Ancient History / Bible Studies

Reason for reading: This year, I’m studying Jesus and the New Testament. This book was loaned to me by Elizabeth, a friend from work. It was given to her by a friend because the author was her professor.

Synopsis: In this short book, Burge guides the reader to interpret Jesus as a storyteller – a teacher who uses allegory and hyperbole to make important points within his own social context. The book is filled with beautiful pictures and several examples of Jesus’ use of hyperbole to teach an important point. Burge provides historical and cultural insight into what Jesus may have been talking about when telling his parables.

My thoughts: I was surprised at how fun this book was. Although it’s quite short, and half of it was pictures, it made me look at Jesus from a interesting new perspective. Of course, I already knew that Jesus used parables and hyperbole to make points, but it was really interesting to read Burge’s cultural analysis of those parables.

The story I found most enlightening was Burge’s interpretation of the fig tree incident. For those of you who don’t recall, the story is related in Mark 11:12-14, 11:20-25; and in Matthew 21:18-22. In my unromantic version, Jesus is hungry, and he sees a fig tree by the road. It’s not fig season, so the tree isn’t bearing any fruit. Jesus curses the poor tree and it withers. I’ve always disliked that story. Despite my cousin Steve’s insistence that fig trees don’t have feelings, and I shouldn’t take the story so literally, I always felt sorry for the tree. Why’d Jesus curse a tree just because it wasn’t bearing fruit in the off-season? (And, yes, Mark clearly states that it wasn’t the season for figs.)

Burge pointed out that the fig tree represented the Jewish state and religion. Throughout the New Testament Jesus repeatedly pointed out the hypocrisy of the Pharisees, who made a public spectacle of themselves fasting, praying, and giving alms; but who did not keep the spirit of religion in their hearts. They prayed for the approval of the people, not for the approval of God. Thus, they were not “bearing fruit.”

Of course, I realize that this insight about the fig tree and the Pharisees is not uniquely Burge’s – in fact I found some interesting articles on the subject after reading Burge’s book (here’s a good one). What’s important is that Jesus, the Middle Eastern Storyteller introduced me to some interesting interpretations that I could look into in more detail later. In that way, this book was a valuable resource for me.

The Annotated Emma, by Jane Austen

Genre: Classic / Regency Romance

Reason for Reading: I’m rereading all of Austen’s novels. I’ve seen these Annotated versions and been tempted to try them out for a while, and this is the one I ended up picking up.

Synopsis: Emma is young, rich, beautiful, and the most important gentleman’s daughter in her neighborhood. When her governess marries and moves away, Emma must find another friend to entertain herself. She chooses Harriet Smith, the love-child of nobody-knows-whom, and boarder at a local country school for girls. Emma, well-meaning but naively self-important, makes a mess by foisting potential suitors upon poor Harriet, while Emma’s old friend Mr. Knightly tries in vain to check Emma’s eager naivete.

My thoughts: I’m a huge fan of Jane Austen. This is the third time I’ve read this novel, and I’ve seen all the movie renditions multiple times. I love watching Emma grow in wisdom throughout the story. And her romance is, in my opinion, the sweetest of those written by Austen. But I recognize that this is a difficult book for many people to get into because of Emma’s painful flaws and poor choices. Another reason that Emma is less appealing to some readers is because the narrator’s perspective is so unique. The POV focuses almost entirely on Emma’s perception of the world, to the point where it is easy to be mislead about what is really occurring since we are only seeing what Emma sees. Emma, especially at the beginning of the novel, tends to be very self-centered and aloof, and so is the narration of the novel. However, even though this POV makes the story harder to get into than the other Austen novels, this is Austen’s most appealing work for character study.

The annotations of this book are lengthy and detailed. Many interesting images and comments are included so that we can visualize antique customs, fashions, and furniture that Austen’s readers would take for granted. That aspect of the annotations was fantastic. The annotations also included a lot of character analysis commentary, such as “Emma thinks such-and-such is happening, which shows you how much she lacks self-awareness at this stage.” These annotations included a lot of spoilers (the reader is warned which annotations include spoilers, but sometimes these warnings were dropped out of the ebook version – so caution should be practiced if you’re reading the book for the first time and you have ebook format). These character analysis annotations were sometimes interesting, but mostly they told me things I’d already knew – either because I was familiar with the story or because I am sensitive to Austen’s nuances. Therefore, I think this annotated version is for you if 1)You are interested in having some historical perspective, 2)You are reading the book for the first time and don’t mind spoilers, 3)You’re re-reading the book, but don’t remember the details and nuances, and/or 4)You just love reading annotations. In other words, I am glad that I read this one book from The Annotated Austen series, because I enjoyed the historical perspective notes, but I probably will not pick up any of the others because I think I got the main idea now.

.

The Ghost Box, by Catherine Fisher

Genre: Middle School Fantasy / Reluctant Readers

Reason for Reading: In exchange for an honest review, this book was provided by Myrick Marketing & Media, LLC via Netgalley.

Synopsis: When Sarah discovers that the ancient tree outside her window is haunted by the ghost of a boy, she is both terrified and fascinated. The ghost boy gives her a beautiful old box and begs her to find a key to open it. But soon, Sarah’s pesky goth step-brother Matt is sticking his nose into her business. Can Sarah find a key to the box without Matt figuring out what’s going on?

My Thoughts: This book was written specifically for middle-school-aged reluctant readers. I’d say the interest level / maturity is for a 10 to 12 year old, but it is second grade reading level. For that target audience, I think this is a wonderful novel! The plot is just the type of story I loved reading when I was in the 4th grade, and the difficult dynamics between Sarah and her step-brother are something that a lot of kids this age will relate to. And, these dynamics end with a message of cooperation, teamwork, and new understanding. So there’s a great message to the story, too. If you are struggling to find books that are age-appropriate for your dyslexic child, I highly recommend this book. In fact, I wish there were a lot more books like this available. The more our reluctant readers enjoy their books, the more likely they are to become readers.